Developing Public Knowledge of Male Breast Cancer

|

|

Abstract A leaflet designed in the essence of exploring public’s knowledge and awareness of male breast cancer (MBC). In addition, to changing societal beliefs relative to breast cancer and provide health awareness, including health preventative measures as well as health practices. In such this will lessen the gender stereotypes associated with breast cancer.

|

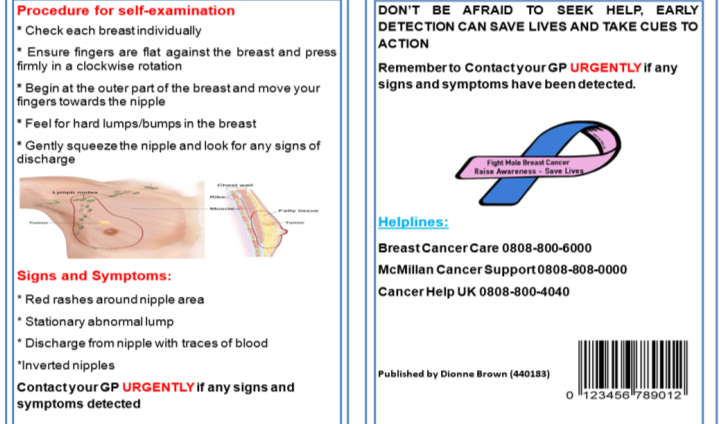

Leaflet 1:

Leaflet 2:

Let’s Wash Our Hands of Gender Bias and Get the Stigma off Our Chest

The rationale behind devising this leaflet is to raise public awareness that both genders are equally prone to breast cancer (BC). Although, Weiss, Moysich and Swede (2005) asserted that the incidence of BC is predominantly affiliated with females, it is important to acknowledge that men can get it too. A research study conducted by Hill et al. (2005) deduced that men were at greater risk of developing advanced BC in comparison with their female counterparts. Even though, Weiss et al. (2005), stated both genders have an equal chance of developing BC. However, research by Hill et al. (2005), challenged this notion and suggested the risk of males’ susceptibility to BC outweighs their female counterparts. The premise of these arguments insinuates that more health awareness is needed to change society’s perception and misbelief on the subject of male breast cancer (MBC), and to make men cognisant of their susceptibilities to the disease.

A study conducted by Thomas (2010), highlights concerns such as: (i) 80% of men were unaware they were susceptible or genetically predisposed to BC, (ii) practitioners had not enlightened them about the malady, (iii) oblivious to identifying other symptoms apart from a lump, (iv) nearly 50% of males were plagued with angst that been diagnose would affect their masculinity. Due to the dearth of knowledge, and given societal conventional beliefs relative to the disease, this warrants an investigation to highlight the importance of raising awareness with intent to dispose of gender biases in public health campaigns, and the dichotomous stigma attached to MBC. This is exemplified in Thomas’ (2010) phenomenological study in which participants proposed that tailored educational awareness should be aimed at men, the lay public, and healthcare providers, as it is vitally important to be well-informed about the risk of MBC through an active health promotion campaign.

Furthermore, after executing extensive research to ascertain if any leaflets to raise awareness about MBC had been previously produced, it was found that there is a paucity of such literature. However, the National Health Service (NHS, 2015) produced an easy read leaflet, but this version is only available online and all the contents are absorbed with female breast cancer (FBC). Unlike the NHS, the Macmillan Cancer Support (MCS, 2015) offered awareness on MBC through various electronic mediums such as, PDF, audiobook and E-book, but was rather limited in the distribution of leaflets. Therefore, there is a gap in raising awareness on MBC by means of distributing leaflets, in comparison with FBC and other types of cancer that receives more attention to promote global awareness that equip the lay public with a wealth of knowledge (Gethins, 2012). Recent studies by Cancer Research UK (CRUK, 2010) and Kovarik (2018), reveal men with BC are under-represented in health promotion campaigns; resulting in a lack of knowledge, self-stigma, embarrassment, and delayed diagnosis. Consequently, metastasised BC increases the risk of premature mortality (Fentiman, 2017). As a result, my leaflet is useful for the purposes of health promotion to ensure men are conversant with identifying signs and symptoms, as taking cues to action can result in early detection, which in turn enhance longevity of life. Correspondingly, Al-Haddad (2010) asserts that healthcare professionals ought to raise awareness, specifically breast-examination, with the aim to achieve early detection and preventing late diagnosis.

Men are the elected audience as research by (Hill, Khamis and Tyczynski, 2005; Al-Naggar and Al-Naggar, 2012), identify that males were at greater risk than females of developing advance stages of BC, yet society’s knowledge and awareness is thus far relatively unknown. In addition, the lack of knowledge and awareness can result in late detection and even increased mortality rate or premature death. Therefore, it is imperative to provide educational intervention to both males and females, so through social interaction with family members, friends or colleagues, everyone will be made aware that BC is not a gender-specific disease as traditionally assumed (United Breast Cancer Foundation, 2016; Fentiman, 2017). Furthermore, the educational awareness, intended to change society’s misconceptions of BC in order to eradicate the embedded stigma and gender bias associated with it (Quaife et al., 2014). As a result, this could adversely affect men’s perceptions of risk, identifying symptoms, prevention in seeking help, delayed diagnosis and succumbing to BC (Ostlin, Eckermann, Mishra, Nkowane & Wallstam, 2006). However, a leaflet is designed with the intention to ensure men become fully informed of how to identify symptoms and taking cues to action.

With hindsight, whilst undertaking this project, I recognised issues such as self /social stigma and gender bias in health promotion campaigns. In relation to health and illnesses, this patient group is known to be reluctant in taking cues to action with seeking help from medical services, which is attributable to self and social stigma (Evans et al., 2005; Hale, Grogan and Willott, 2010). Men being exposed to societal stigma of association with female characteristics can affect the sufferer’s willingness to seek and accept help for a disease that poses risk of questioning their masculinity. Consequently, this can aggravate behavioural responses such as social withdrawal due to self-stigma, which can induce self-stigma and psychological difficulties according to (Geng et al., 2018). Midding et al., (2018) support this notion asserting; that being in receipt of external stigma can lead to becoming lonely and being socially excluded. The impact from stigma and labelling of having a feminine disease can have an adverse effect on the individual’s psychological wellbeing due to the perception of the disease.

Furthermore, males have been victims, in essence, of underrepresentation in scientific researches, funding and health promotion where BC is concerned, which may have contributed to MBC been less understood and treated effectively by clinicians (Fentiman, 2017). Also, previous studies by Girnius and Nahleh, (2006); Thomas, (2010) showed most of the available information relative to BC was tailored towards women and the limited researches on MBC are extrapolated from research carried out on females. A further research conducted by Hoyt and Rubin (2012), found that previous scientific studies have failed to take into account the individual differences in anatomy and the gender differences in gender non-specific studies when investigating any types of cancer. Despite the varied gender differences in BC, the gynocentrism is evident in scientific research; existing literatures and the therapeutic treatments are from gender specific experiments (Breast Cancer Care, 2018; Hamberg, 2008). However, a preliminary test showed that local BC charitable organisations and health care facilities such as; Macmillan, The Christies, The Maggie’s centre, GP Practice, walk-in-centre are all guilty of gynocentrism whereby females remain the central focus in health promotions including researches in oncology (Thomas, 2010).

Based on the findings from preliminary test evidenced or demonstrated that the disparity between the mass media campaigns to promote MBC in comparison to FBC is currently overlooked (Nemchek, 2018). Critics highlighted it is an overlooked issue that males are excluded from public health campaigns including clinical trials by charitable and public health services to raise awareness of MBC (Gómez-Raposo et al., 2010; Speirs & Winsor, 2018). However, devising this leaflet is introduced as an alternate means to help raise awareness, through the distribution of leaflets to local amenities, charitable organisations, local health facilities, gyms, bars including their lavatory. In addition, there are no previous medical leaflets relating to MBC in the UK, and the majority of the readily retrievable information that can help raise awareness is accessible online and are yet absorbed within FBC. The method of devising a hard copy leaflet takes into consideration the diverse nature and individual differences of my target audience, for instance, who may not be technologically savvy or have resources to access information online.

My leaflet presents a list of procedures to carry out a breast self-examination (BSE) along with a list of common symptoms to enable the layperson (men) to complete a successful BSE and aiding men to identify the signs and symptoms. Also, within the text clear instructions were provided to urge the patient to contact their general practitioner if any symptom were detected during self-examining. Research by Al-Naggar and Al-Naggar (2012) identifies the importance of educating men about MBC and how to perform BSE, because early detection can save lives. The Male Breast Cancer Coalition (MBCC, 2018) concurs providing health awareness about BSE is useful to detect early signs of BC in men, despite the popularity of promoting BSE among females. Also, free helpline numbers for BC organisations are provided, in the leaflet so that anyone in need of assistance can receive: specialised 1-1 support, answers to any BC related queries and emotional support prior to and post diagnosis to help in such a difficult time (Breast Cancer care, 2013).

The leaflet remains focused on its aim to reach a populace that receives disproportionately low levels of attention in health campaigns and scientific investigations. In order to relay the message in a way that is appealing and to reach a wider audience this leaflet is an unprecedented step to raising awareness of the issue of MBC. As said by Robertson (2008) a leaflet is an efficacious way to convey information to the targeted audience and it is becoming increasingly popular among promotion of health campaigns. Hence, the approach taken to address the highlighted issues such as lack of MBC awareness, gender bias and stigma is all incorporated in the design of the leaflets. Therefore, to reach the targeted audience identical leaflets with two different backgrounds which made use of language that is age appropriate, easy to read, inclusive, comprehensible, interesting and succinct.

My leaflet was designed based on feedback from a preliminary test, both leaflets are said to be appealing, but decisions between leaflet 1 and 2 were equally divided. For instance, leaflet 1 is deemed appealing and it enhances the topic in discussion more, while leaflet 2 was desired because the background colour is more masculine and subtle. However, equally, both leaflets are appealing and the construction takes into consideration individuality in preferences. Similarly, it is said, the words used in the title is accentuated as the title takes into consideration existing social issues like gender bias and stigma. However, the information included is not overbearing and gives the targeted community a sense of inclusiveness without feeling excluded and marginalised from health promotion which can result in gender bias (Freedman & Partridge, 2017).

In addition, the BC symbols used to make leaflet more gender neutral and recipient can feel a sense of belonging and togetherness without feeling excluded and at the same time working on gender equality in health promotion of MBC. Moreover, my leaflet includes contact numbers for BC charitable organisations helplines, which has provided dedicated service by qualified specialist support, assistance, health advice and reassurance to persons who need it. The topic have been carefully chosen to make it known that health promotion is a social problem as gender bias is rampant/embedded in society. According to, Breast Cancer Care (2018) transgender males will be excluded from BC screening.

Moreover, practical difficulties linked to this subject are whether men will accept and use the information provided in the leaflet to promote their general health and seek medical help upon discovering signs or symptoms of BC. Jahan (2012) argued that promotional health should have an aim or vested interested to aid people to identify the usefulness of engaging in healthy behaviours. Therefore, this health promotion leaflet can encourage men to take cues to action once perceived susceptibility to BC is acknowledged; because if caught at a precancerous stage it can reduce their risk of ineffective treatment. More research and health promotion is needed on MBC, because research suggests there is a lack of personalised themes on websites for MBC, and there is a gap in knowledge (Korde, 2015).

Furthermore, the application of the Health Belief Model (HBM) was used in the formulation of this leaflet. For this model aims to offer an explanation of reasons why people are motivated to participate in health related behaviours based on conceptualised susceptibility, ramifications on quality of life and perceived effectiveness of interventions (Henshaw & Freedman-Doan, 2009). The bio-psychosocial model, could be used to examine other factors that affect the sufferer’s health and wellbeing. It is essential to apply other theories to explore other impacts on the quality of life as this would lessen the stigma associated with the public’s perception and allow society to have a dichotomous view of the susceptibility rates of BC.

In retrospect, my leaflet is successful in aiming to reach a community or audience that lacks awareness of MBC and become conversant with the fact that BC is not a gender specific illness. A positive outcome of this was done by providing vital information within both leaflet that aims to enrich the knowledge of men, on how to perform routine practices in identifying unusual changes in the breast. This is effective in educating and helping men to successfully engage in healthy behaviours. Zarcadoolas, Pleasant and Greer (2009), concur that a lack of awareness contributes to harmful behaviours. Furthermore, after being granted permission to utilise my local healthcare facilities and leisure amenities to distribute my leaflets, thus increase the probabilities of reaching the target audience and can help to influence change. Guttman (2017) argued that aiming to influence the public’s opinion on the way of life creates ethical issues. However, based on positive feedbacks from the public, including specialists in oncology at The Christie Trust, along with my local healthcare centres, and the request of copies of my leaflet indicates that the idea, aims and target of the leaflet are well received by the public.

In operationalising this project, I have acquired a wealth of knowledge about MBC and in devising such an informative leaflet I recognised that social awareness of the disease is sparse, influencing gender bias and stigma. Therefore, it would be beneficial to convey educational awareness in other regions of the UK. As well as the majority of men are excluded from government funding and scientific researches. I have also learnt that some men from my targeted audience may be reluctant in accepting the information given, but optimistically the education and awareness will inevitably change their perception and attitudes towards acknowledging MBC. My product could improve by including different types of ethical backgrounds.

References:

-

Al-Haddad, M. (2010).

Breast cancer in men: the importance of teaching and raising awareness

.

Clinical journal of oncology nursing

,

14

(1). -

Al-Naggar, R. A., & Al-Naggar, D. H. (2012).

Perceptions

and opinions about male breast cancer and male breast self-examination: a qualitative study

.

Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention

,

13

(1), 243-246. -

Breast Cancer Care. (2018).

Trans patients might lose out on cancer screening

: Retrieved from

https://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/about-us/news-personal-stories/trans-people-missing-out-breast-cancer-screening

-

Cancer research UK. (2010).

Why are men more likely to die from cancer?

Retrieved from

https://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2009/06/15/why-are-men-more-likely-to-die-from-cancer/

-

Evans, R. E., Brotherstone, H., Miles, A., & Wardle, J. (2005). Gender differences in early detection of cancer.

Journal of Men’s Health and Gender

,

2

(2), 209-217. -

Fentiman, I. (2017).

Male Breast Cancer

: Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04669-3 -

Freedman, R. A., & Partridge, A. H. (2017).

Emerging data and current challenges for young, old, obese, or male patients with breast cancer

. -

Gethins, M. (2012).

Breast cancer in men

, 104 (6): 436-438 -

Gómez-Raposo, C., Zambrana Tévar, F., Sereno Moyano, M., López Gómez, M., & Casado, E. (2010).

Male Breast Cancer

.

Cancer Treatment Reviews, 36

(6), 451-457. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.002 -

Guttman, N. (2017).

Ethical issues in health promotion and communication interventions

. -

Hale, S., Grogan, S., & Willott, S. (2010).

Male GPs’ views on men seeking medical help

: A qualitative study.

British Journal of Health Psychology

,

15

(4), 697-713. -

Hamberg, K. (2008). Gender bias in medicine.

Women’s health

,

4

(3), 237-243. -

Henshaw, E. J., & Freedman‐Doan, C. R. (2009).

Conceptualizing mental health care utilization using the health belief model

.

Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice

,

16

(4), 420-439. -

Hill, T. D., Khamis, H. J., & Tyczynski, J. E. & Berkel. H.J (2005).

Comparison of Male and Female Breast Cancer Incidence Trends, Tumour Characteristics, and Survival.

Annals of Epidemiology

,

15

(10), 773-780. -

Hoyt, M. A., & Rubin, L. R. (2012).

Gender representation of cancer patients in medical treatment and psychosocial survivorship research

.

Cancer, 118

(19), 4824-4832. doi:10.1002/cncr.27432 -

Jahan, S. (2012).

Health Promotion: Opportunities and Challenges

.

Journal of Biosafety & Health Education

. -

Korde L. A. (2015).

Male Breast Cancer: A Study in Small Steps.

The oncologist

,

20

(6), 584-5. -

Kovarik, W. M. (2018). Male Breast Cancer: A Healing Path of My Own. Retrieved from

-

Macmillan Cancer Support (2015).

Understanding breast cancer in men.

Retrieved from

https://be.macmillan.org.uk/be/p-19027-understanding-breast-cancer-in-men.aspx

-

Midding, E., Halbach, S. M., Kowalski, C., Weber, R., Würstlein, R., & Ernstmann, N. (2018).

Men With a “Woman’s Disease”: Stigmatization of Male Breast Cancer Patients-A Mixed Methods Analysis

.

American journal of men’s health

,

12

(6), 2194-2207. -

Nahleh, Z., & Girnius, S. (2006).

Male Breast Cancer: A Gender Issue

.

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology

,

3

(8), 428. -

National Health Service. (2015).

Breast cancer and how to spot it

. Retrieved from -

https://www.wsh.nhs.uk/CMS-Documents/Patient-leaflets/BreastCare/6155-1Breast-Cancer-and-how-to-spot-it-easy-read-leaflet.pdf

-

Nemchek, L. (2018).

Male Breast Cancer: Examining Gender Disparity in Diagnosis and Treatment

.

Clinical journal of oncology nursing

,

22

(5), E127-E133. -

Östlin, P., Eckermann, E., Mishra, U. S., Nkowane, M., & Wallstam, E. (2006).

Gender and health promotion: A multisectoral policy approach.

Health promotion international

,

21

(suppl_1), 25-35. -

Quaife, S. L., L J L Forbes, Ramirez, A. J., Brain, K. E., Donnelly, C., Simon, A. E., & Wardle, J. (2014).

Recognition of cancer warning signs and anticipated delay in help-seeking in a population sample of adults in the UK

.

British Journal of Cancer, 110

(1), 12-18. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.684 -

Robertson, R. (2008). Using information to promote healthy behaviours.

London, United Kingdom: King’s Fund

. -

Speirs, V., & Winsor, V. (2018).

Male Breast Cancer.

Retrieved from

https://www.nursinginpractice.com/article/male-breast-cancer

-

The Male Breast Cancer Coalition. (2018).

Breast Self-Exams

: Retrieved from

-

Thomas, E. (2010).

Men’s awareness and knowledge of male breast cancer

.

AJN.

The American Journal of Nursing,

110

(10), 32-37. -

United Breast Cancer Foundation. (2016).

Male Breast cancer: the Stigma

. Retrieved from

-

Weiss, J. R., Moysich, K. B., & Swede, H. (2005).

Epidemiology of male breast cancer

.

Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers

,

14

(1), 20-26. -

Yang, N., Cao, Y., Li, X., Li, S., Yan, H., & Geng, Q. (2018).

Mediating Effects of Patients’ Stigma and Self-Efficacy on Relationships between Doctors’ Empathy Abilities and Patients’ Cellular Immunity in Male Breast Cancer Patients.

Medical Science Monitor

,

24

, 3978-3986. -

Zarcadoolas, C., Pleasant, A., & Greer, D. S. (2009).

Advancing health literacy: A framework for understanding and action

(Vol. 45). John Wiley & Sons.

Gender Representation of Cancer Patients in Medical

Treatment and Psychosocial Survivorship Research

Appendices for Group Discussion

One of the requirements for this module entails partaking in a group discussion for the required dates, Friday 15th December 2017, Friday 26th January 2018 and Friday 23rd February 2018. However, unfortunately due to unforeseen medical issues leading to several months of hospitalisation, this has impacted on my ability to actively participate in the group discussions.

PLACE THIS ORDER OR A SIMILAR ORDER WITH ALL NURSING ASSIGNMENTS TODAY AND GET AN AMAZING DISCOUNT

PLACE THIS ORDER OR A SIMILAR ORDER WITH ALL NURSING ASSIGNMENTS TODAY AND GET AN AMAZING DISCOUNT